Face to Face with a Portrait

FACE TO FACE WITH A PORTRAIT

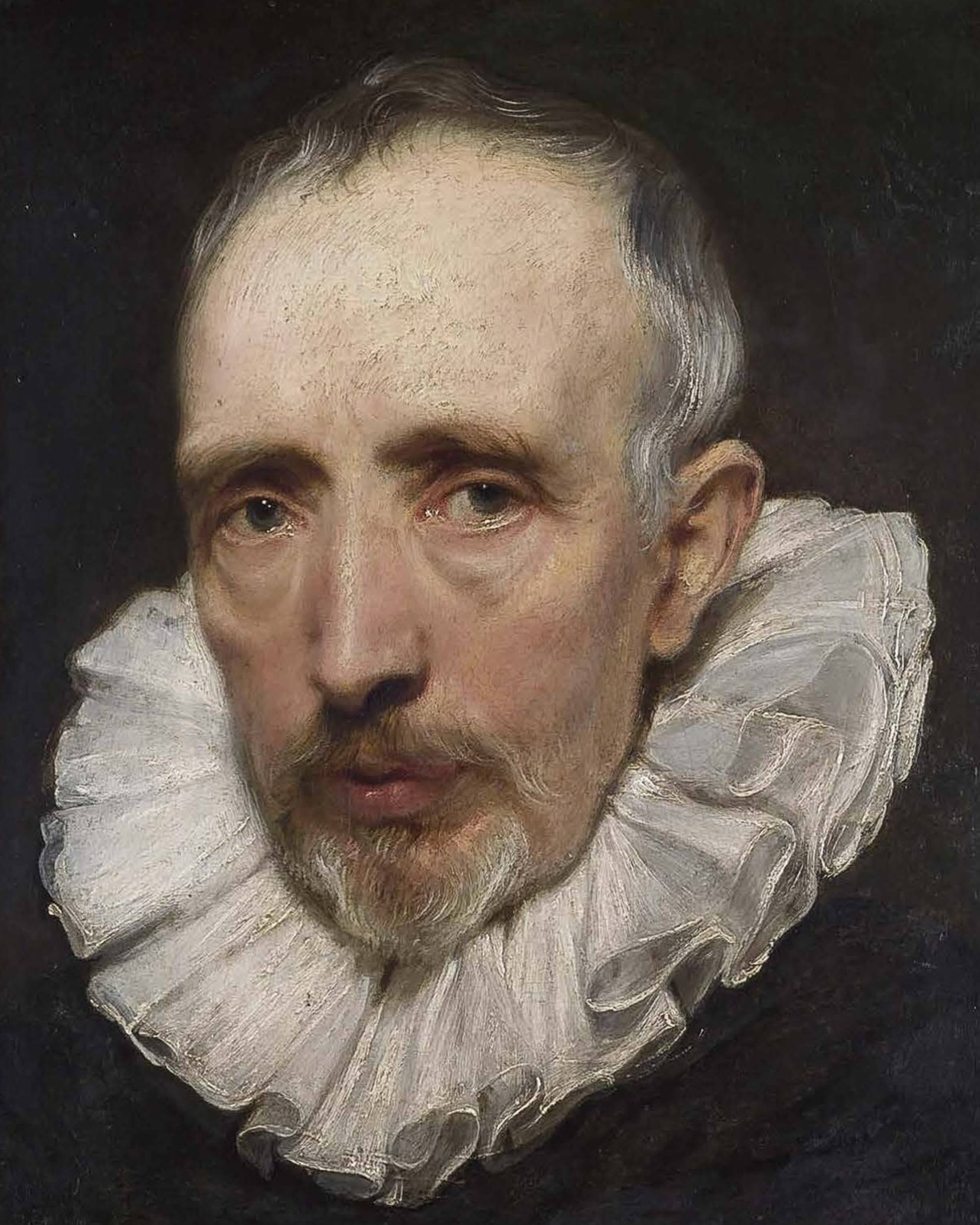

Héctor Abad FaciolinceAn educated eye, though it remains alive and penetrating, can eventually glaze over, wearied by all the art and beautiful things it has seen. It is the melancholy of Civilizations as they gain self-awareness. And it is essentially this, and more, that a young poet from a distant land glimpsed in the gaze of Cornelis van der Geest, a seventeenth-century spice merchant, patron of the arts, and collector from Antwerp, across a distance of three centuries. Anton van Dyck painted a memorable portrait of van der Geest at the threshold of old age, a moment when an homme civilisé is at his prime. And Colombian novelist Héctor Abad Faciolince wrote poetry about it. The conversation between the living writer and the long-dead Flemish connoisseur continues here, many years after they first locked eyes.