Venetian Hieroglyphics

VENETIAN HIEROGLYPHICS

Monica De Vincenti, Simone Guerriero

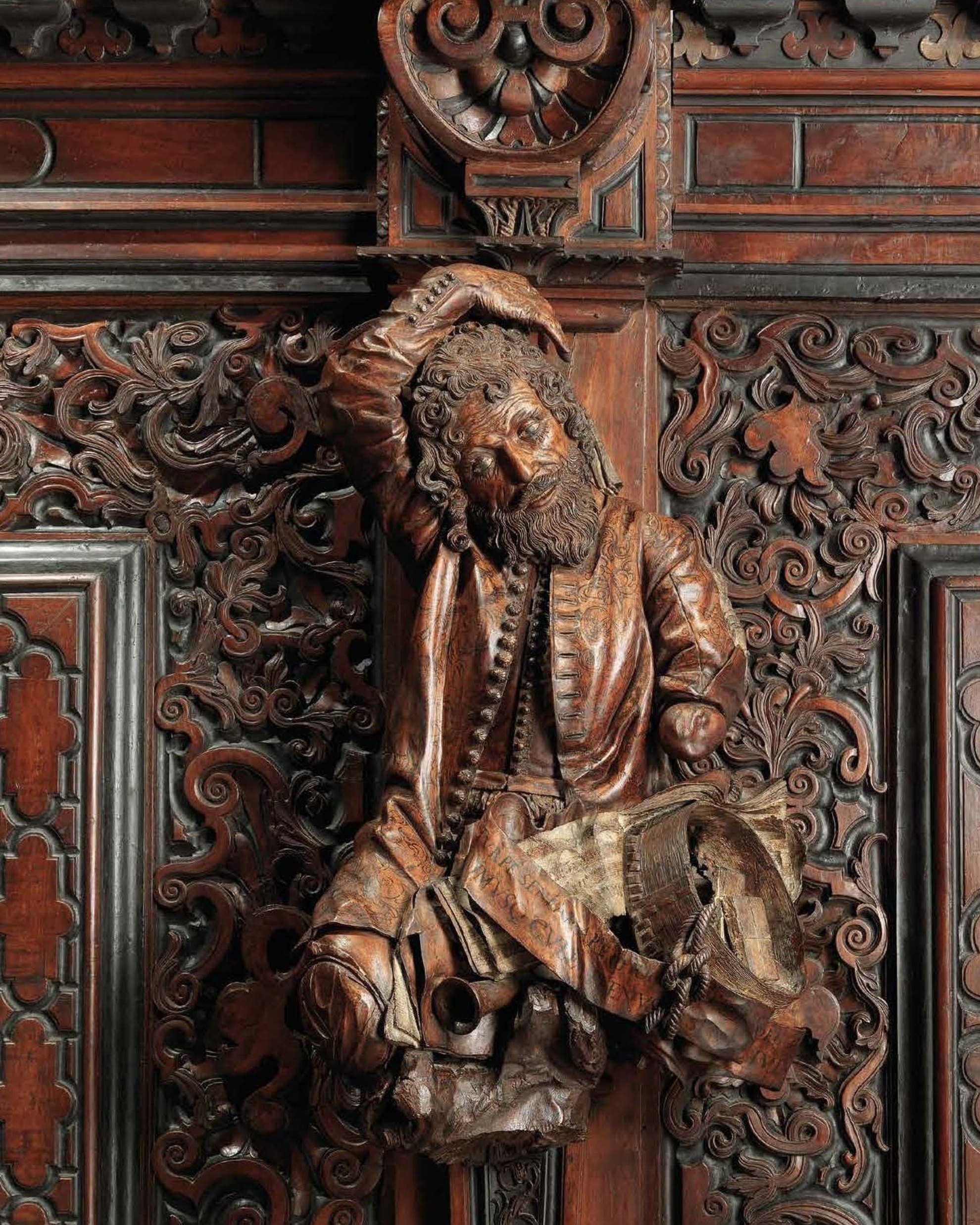

Visitors to the Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice, not unreasonably attracted by the major artist, Tintoretto, often forget, in the upper room, to cast a glance at the frames of those huge canvases. But whoever deigns to pay attention to the carvings of Francesco Pianta cannot fail to be struck by their enigmatic strangeness and by the mixture of violence and refinement in their technique. Flasks, guns, chains, hampers, books, masks, a donkey’s head here, a severed human foot there, reading-desks, sieves, brushes, ropes and hammers, jugs, musical instruments, what is the meaning of all this odd assortment accompanying figures of athletes and dons, of people naked or else wrapped in their cloaks, of lusty fellows or maimed wretches, all carved in a mellow, glossy, worm-eaten wood? No doubt this work belongs to the seventeenth century; in any other epoch of the past, this would have been the work of a madman. But in the seventeenth century, in the century of Don Quixote and of Manzoni’s Don Ferrante, there was a razón de la sinrazón, a method in madness.

Mario Praz