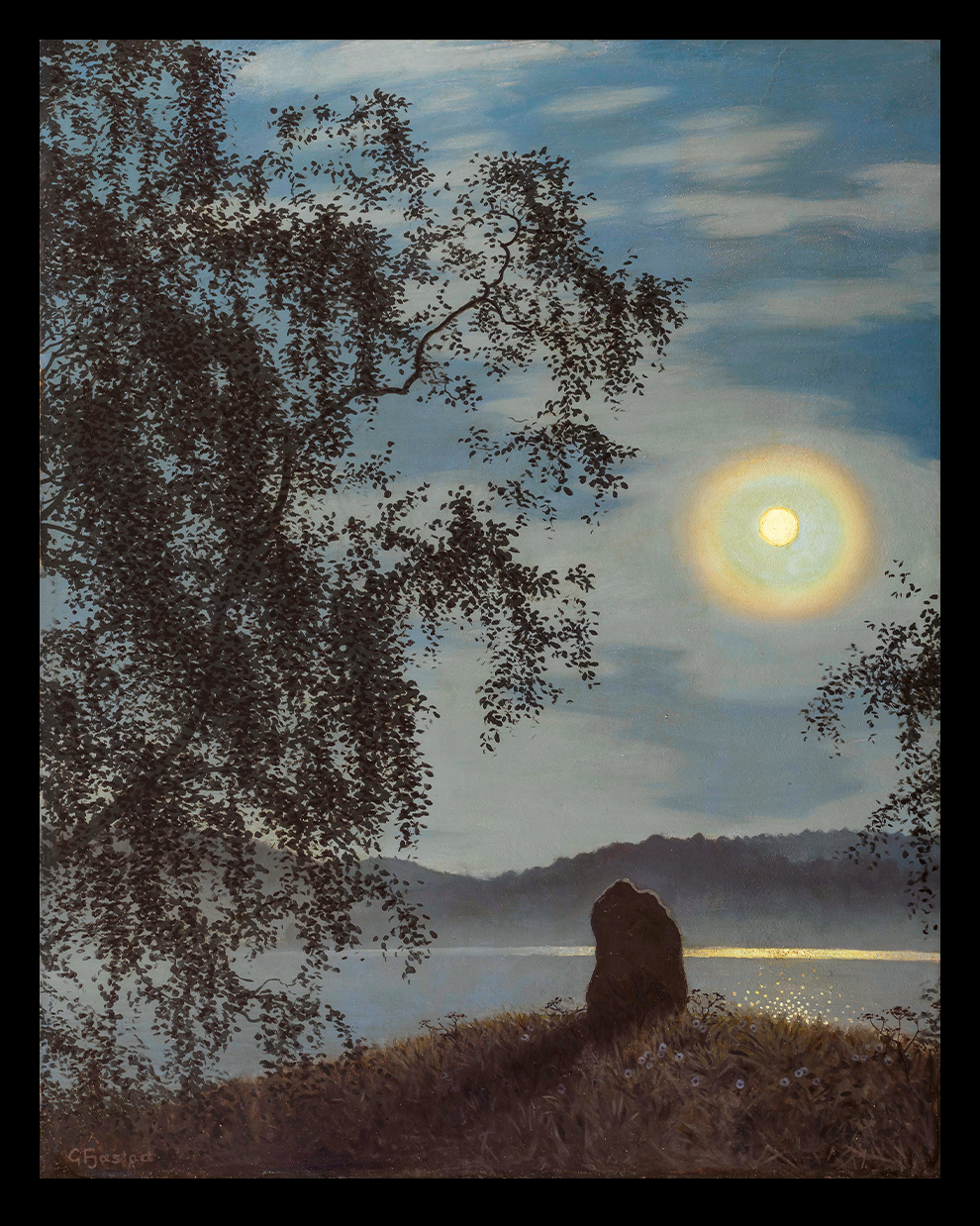

In many ways, Fjæstad was a solitary figure. His painting is undoubtedly related to several movements in Europe, such as the Synthetists and Pointillists of Post-Impressionism in France, the Vienna Secessionists, and the Nordic National Romantics. It also drew inspiration from the Japanese woodblock prints popular in Western Europe in his day. What sets him apart from most artists of his time, however, are his use of close perspective and the seemingly harsh cropping of his compositions. In a painting such as Snowy Landscape, the scene is framed in a way that condenses the pictorial space. It might have seemed claustrophobic, were it not for the indirect opening at the top left that lets in the light reflected by the snow in the center. Here, Fjæstad is more closely related to the early nineteenth-century German Romantics than to his contemporary Nordic National Romantics. The image can certainly be regarded as a kind of Nordic national archetype, but the intentions for the viewer are similar to those of Caspar David Friedrich. The painting is divided into foreground (the snow-covered road and the ground beside it), middle ground (the dense spruce forest), and an indistinct background, discernable only through the light that enters, establishing a connection between the viewer and everything beyond. Like Caspar David Friedrich in Monk by the Sea (Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin), Gustaf Fjæstad has reduced the scene to a minimum, seeking to present pure nature. As in Freidrich’s composition, the viewer is given a platform in the foreground from which to contemplate the depths of the forest and the alluring, indistinct distant horizon.

Also similar to Friedrich’s work, and unlike many Swedish national romantics, the scene and terrain are recognizable, but the image does not depict any specific, named place.

Fjæstad was an artist of his time. In the 1890s, several Swedish artists moved from the cities to the countryside. Carl Larsson moved to Sundborn in Dalarna and Anders Zorn relocated to Mora in the same province. Gustaf Fjæstad and his wife Maja, also an artist, moved to Värmland and Lake Racken. While Larsson and Zorn sought out the north for its lifestyle and folk culture, it was unspoiled nature that attracted Fjæstad. Värmland was one of the centers of Swedish national Romanticism. The author Selma Lagerlöf came from Värmland and worked there, and the poet Gustaf Fröding sought refuge there. Its deep forests nourished the imagination and fostered creativity. Indeed, a significant part of Fjæstad’s life consisted of wandering in the forests. He devoted himself to detailed and time-consuming observation that later formed the basis for his painting. During his walks, he learned to read nature and to interpret the cyclical signs of weather and seasonal changes. Many of Fjæstad’s images are based on the sharpest observation – you almost feel the temperature of the place. This is particularly true of his winter images, which often depict scenes with trees and ground covered in thick layers of snow. Nature appears stylized, as in the Japanese woodcuts that Fjæstad and his contemporaries admired.

In Snow from 1920-21, for example, the formal organization is so striking that one forgets that nature sometimes actually looks like this, when there is no wind and the snow has been left undisturbed. Fjæstad, like many other artists, understood that man’s relationship with nature is based on rarity and authenticity, and, like the Romantics, sought to experience the simple as overwhelming. The poet Novalis describes this approach in one of his fragments from 1798: “The world must be romanticized. In this way one will again discover the origin-meaning. […] I romanticize the world to the extent that I give the common a higher meaning, the ordinary a mystery-laden aspect, the known the dignity of the unknown, and the finite the luster of eternity…”1 Fjæstad is probably the artist of his generation who most clearly romanticizes nature in order to make others see it in its most fantastic and engaging form. Numerous examples of this can be found in his paintings depicting scenes where the temperature has dropped and approaches zero. The cold, powdery snow becomes heavy and wet, melting into new, softly organic shapes.

Goethe, for example, in The Sorrows of Young Werther, describes the main character sitting by a river watching the water carry away his ideas of distant things as it flows by. Like his depictions of snow, the water in Fjæstad’s paintings varies with the weather and the turn of the seasons. We experience water frozen into ice, the meltwater of the spring flood, and the clear summer water of the lakes of Värmland. In one of the artist’s most beautiful water paintings, the temperature has dropped and columns of steam rise from the water toward the sky – the water itself seems to exude what the Romantics regarded as the spirit of nature, released into the air that humans breathe. The painting is called The First Breath of Cold on the Water (SMK, Copenhagen) and was created in 1895.

I would like to conclude with a passage from Gaston Bachelard’s Water and Dreams – an Essay on the Imagination of Matter, which summarizes how Gustaf Fjæstad’s anonymous yet infinitely rich water and forest scenes function: “I was born in a country of brooks and rivers, in a corner of Champagne, called Le Vallage for the great number of its valleys. The most beautiful of its places for me was the hollow of a valley by the side of fresh water, in the shade of willows...My pleasure still is to follow the stream, to walk along its banks in the right direction, in the direction of the flowing water, the water that leads life towards the next village...Dreaming beside the river, I gave my imagination to the water, the green, clear water, the water that makes the meadows green. ...The stream doesn’t have to be ours; the water doesn’t have to be ours. The anonymous water knows all my secrets. And the same memory issues from every spring.”2

Carl-Johan Olsson

Curator of Nineteenth-Century Painting, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

NOTES

- Novalis (Friedrich von Hardenberg), Fragmente und Studien, 1797-1798, 37.

- Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams – an Essay on the Imagination of Matter (The Pegasus Foundation, Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture, 1983).