For one thing (among many) seems to me intolerable to an artist: to lose the feeling of starting something fresh.

Cesare Pavese, This Business of Living: Diaries 1935-1950, October 17, 1935

1. Late at night, the two painters conspired to do something nice for their host (who was fast asleep) by frescoing the living room that had been the setting for their copious libations earlier that evening. By morning, the walls were covered with tangles of black, blue, and red lines from which “suffering human figures” emerged, as the youthful artists explained to the homeowner, who now stood aghast. “We all owe a debt of gratitude to Siqueiros,” they confessed in unison. “He gave us our sense of social rebellion,” said the artist with the noble profile of the Aymara people. “He embodies the essence of artistic dissent,” chimed in the other. They added that Siqueiros had transformed the purely rhetorical Grito de Dolores – the cry that launched the movement for independence traditionally echoed by sitting Mexican presidents in homage to Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla – into a collective roar far more powerful than Munch’s Scream. Siqueiros had succeeded in giving pictorial form to the clamor of the disenfranchised indigenous masses, the first young artist remarked. His murals expressed the very roots of Latin American art, the second declared. Then they demanded payment for their work (executed, they said, “with fingers and sticks, just like Pollock”). The homeowner’s response was swift. He strode out of the room and swept right back in with a leveled shotgun: “Buckshot!” he roared. “That’s the payment you deserve for defacing this room!” Those two fledgling painters were Armando Villegas and Fernando Botero [henceforth, “the Maestro”], and this anecdote reached my ears through Botero’s own retelling.

2. One summer morning thirteen years ago, a slender man with a jet-black helmet of hair climbed the slope leading up to the Maestro’s house. He was ushered into the studio and seated in front of the old sofa reserved for the artist. An imposing portrait dominated the high wall above it: a painting that collectors had sought for years to acquire, in vain. It depicted the Infanta Margarita Teresa, and was modeled after the Viennese portrait by Velázquez (Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Blue Dress, 1659), though it was larger and more flamboyant than the original. The unlikely contrast between the light blues of the dress and the dark blue background, accentuated by the princess’s golden hair, gave her a playful air, as though she were a fairground doll. Yet, the man thought, beyond its light-hearted appearance, the painting was imposing – a testament to stylistic and esthetic maturity. Velázquez’s spirit hovered, but had been subjected to the Maestro’s creative vision, so dominant here that one forgot the original source. When did the break from the Renaissance Masters occur? At what point did it become the Baroque? The man continued to study the painting: it was suffused with an airy grace, due not only to its size and color but also the treatment of the figure, balanced though rather contrived. She resembled the Virgin of the Rosary of Pomata – not in terms of her features but in the voluminous profusion of her dress and the abundance of ornaments, a hyperbolic effect the Maestro had attained with great care, just as Góngora had done in composing the Soledades, embellishing each motif. In other words, the painting revealed an original rhetorical structure, one built on “augmentative” figures (like auxesis and amplificatio) rather than “imagistic” ones (such as allusion, metaphor, or wit). Using this approach, the Maestro had reinvented the Baroque in its “colonial” sense, evoking memories of the Ángeles Arcabuceros (musket-toting angels) of Cuzco. Though he’d started from Renaissance models, as seen through the lenses of Expressionism and Cubism, over time – how long? six, seven years? the man wondered – he had arrived at a more expansive and seductive style. To achieve this, he had renounced avant-garde ideology and dedicated himself instead to redeeming that most popular of artistic genres: the Baroque. He had grasped its untapped modernity, reframing it by means of a wholly new figurative language that recalled Quevedo’s picaresque style more than Góngora’s Culterano ornamentalism. The visitor’s thoughts were interrupted by the arrival of the old artist himself. The Maestro immediately wanted to examine the printing proofs that his guest – a publisher – had brought with him. The book concerned the Maestro’s “search for style” at the beginning of his career, specifically during the fifteen years between 1949 and 1963, and it was profusely illustrated with little-known or forgotten works of his that were nonetheless milestones in one of the most admired artistic journeys of the twentieth century. As the Maestro leafed through the book, glancing at each image with great surprise, he muttered in disgust, “¿Qué es esto tan feo?” (“What is this hideous stuff?”).

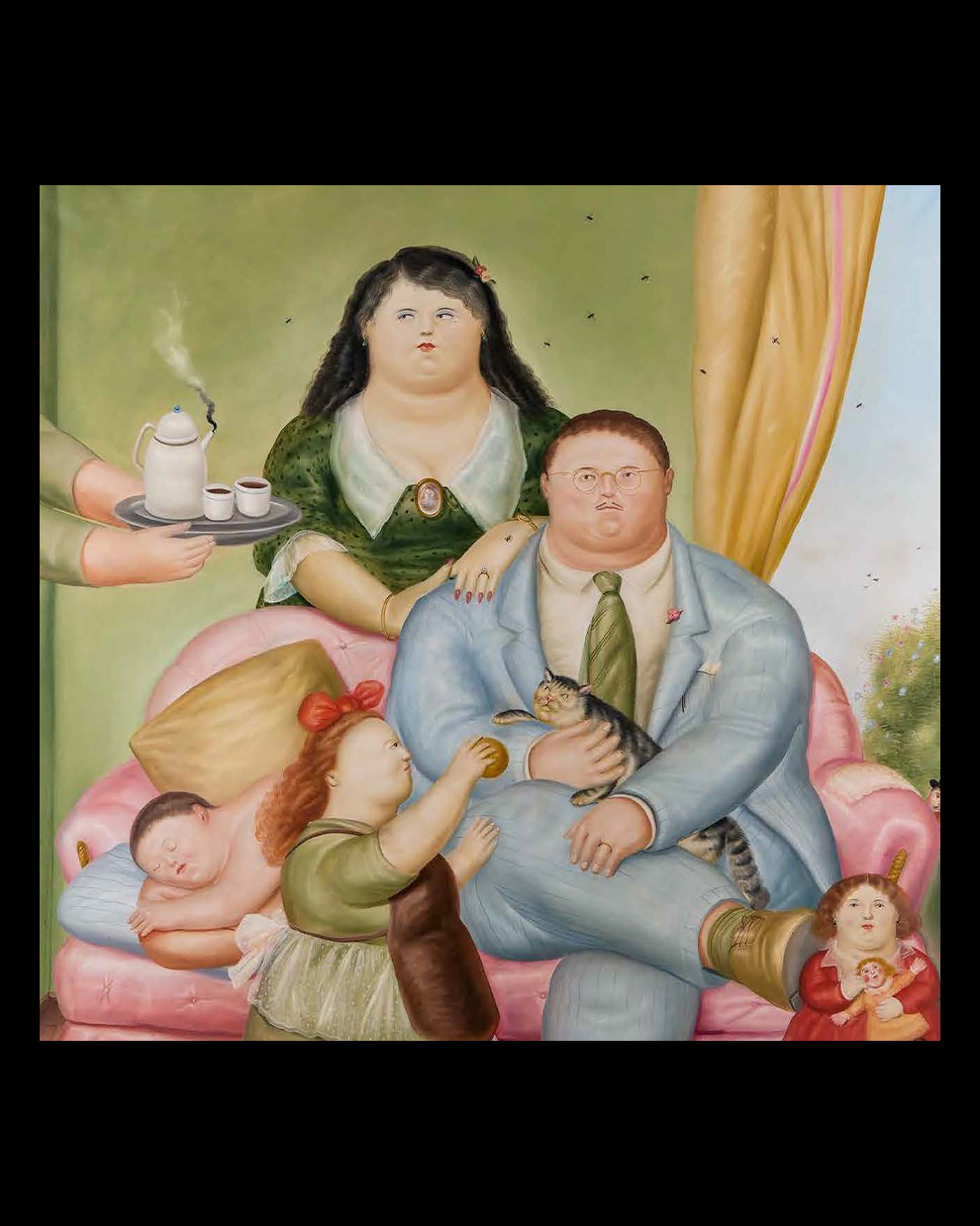

3. A recent sample survey conducted by a Swiss research group confirmed the existence of a link between the love of art and art-lovers’ appetites. Indeed, after lingering over large-format reproductions of works by Alberto Giacometti, most participants reported a loss of appetite. Sadly, no investigation has been undertaken into the reverse reaction: that is, the response of gastric mucosa in the presence of, say, Charles Mellin’s Portrait of a Gentleman (ca. 1630), which masterfully captures the proud corpulence of Gen. Alessandro dal Borro. Might there be some connection between the creative act and the creator’s mechanoreceptors – that is, between the artwork and the artist’s diet? When applied to the Maestro, that supposition leads to another question: can we postulate a link between his well-known artistic choices and his gaunt physique as a young man? Let me not dwell on the point, but it hardly seems wrong to muse on the origins – both dietary and esthetic – of thinness and corpulence in the artistic domain. It has been said that the fragility of Schiele’s bodies constitutes, on one hand, the Expressionist counterpart to the languor of the Secessionist style and, on the other, an allegory of Vienna’s sparse population during World War I. In turn, the figures depicted by Francis Gruber and other “miserabilist” painters supposedly allude to the social and existential conditions in the France of Sartre and Camus. Whatever the findings, one might suppose that certain painters’ leanness heightened their acerbity – or, if you will, their taste for satire and distortion. As for the Maestro, the beginnings of his career unfolded between two extremes in expression: the skinniness of his early figures and the corpulence of his later ones, from the bony fishermen of Tolú to the plump characters that emerged after his trip to Italy. There is no missing the fact that, until the mid-1960s, corpulence in the Maestro’s paintings tended towards caricature and the grotesque, verging on deformity, whereas it later turned amiable and graceful. From somber and ponderous, it became colorful and “light” and from mournful, it grew joyous, a definitive shift that was echoed in one of his equally assertive maxims: “Art was created to bring pleasure.” That maxim aligns to an exemplary degree with his mature works but not with his early output, marked instead by that malaise of existence – both individual and social – so prevalent in the painting of the 1950s (the same malaise that would lead to the rise of abstract Expressionism and, conversely, to the crisis of figuration). The Maestro would later say that his career unfolded in solitude, swimming against the current – that is, against the trends of contemporary art – and it is impossible to dispute the point. This metaphorical swim seems to have metaphorically strengthened his muscles, as if his weight gain reflected his search for happiness. While in the early stages of his expressive journey, leanness corresponded to creative fury, over time, the Maestro, having freed himself from self-imposed penances and vows, reconciled himself, so to speak, with “the joys of the table.” And it is precisely in dining rooms, living rooms, and gardens that so many of his characters come together, as if to sing in unison the words of Lorenzo the Magnificent’s canzone: “How wondrous beautiful is youth, yet fleeting, so soon gone, in truth! He who will, let happy be, the morrow has no certainty.”

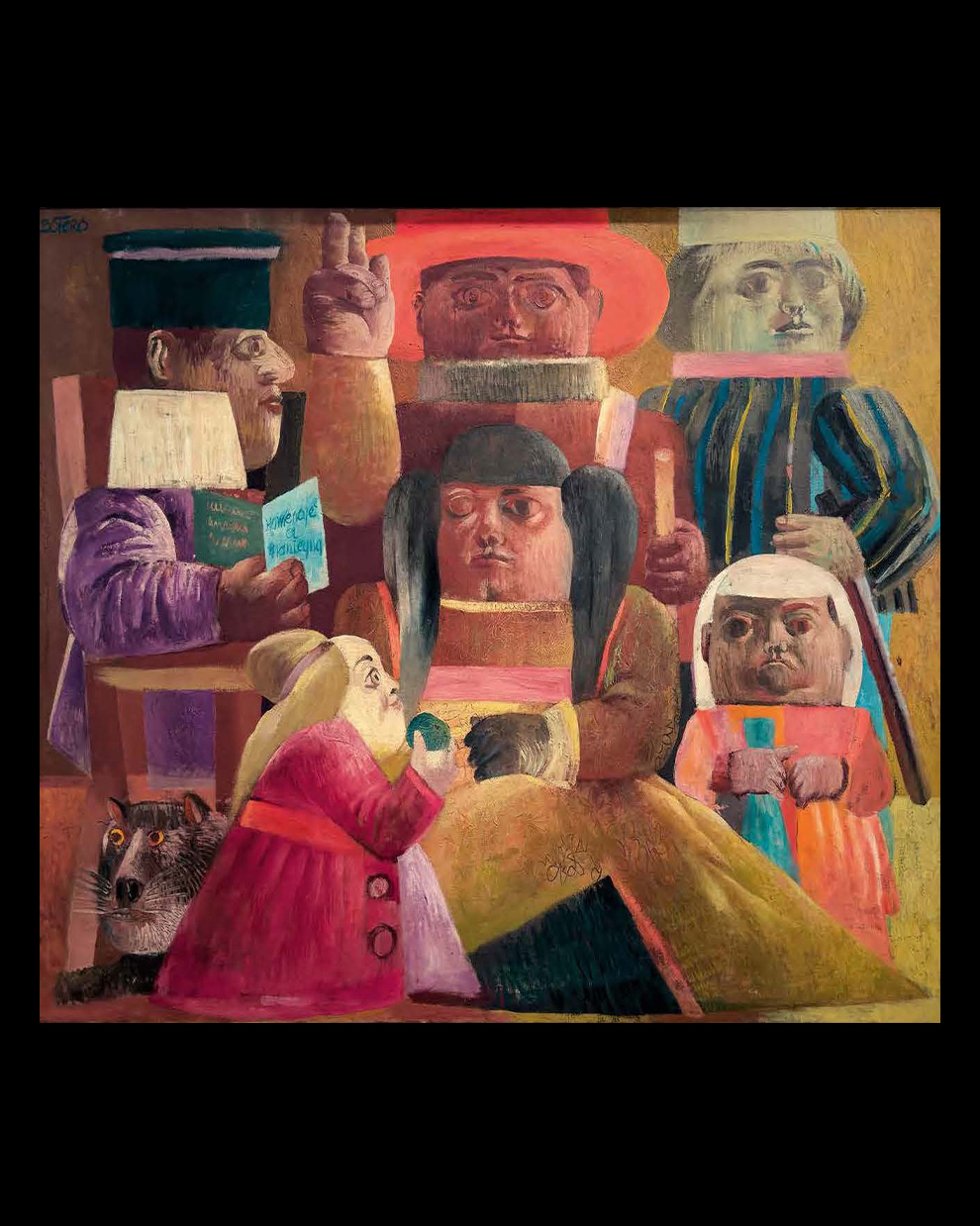

4. To embody the adage “beata solitudo, sola beatitudo” (“blessed solitude, only happiness”), both time and space are essential. Personally, I basked in solitude for years on a mustard-colored leather sofa with a bleached armrest. It was tucked into a secluded corner of the attic that served as my studio – a vast, multi-sectioned space with a high, steeply pitched ceiling, characteristic of the Tudor-style houses overlooking Olaya Herrera Park in Bogotá. The sofa was surrounded by tall bookshelves that ensured isolation: sitting or lying on it, immersed in reading or simply absorbed in thought, I enjoyed the scent of the leather and the softness of the upholstery. The only impediment to absolute bliss was that unsightly discoloration. Directly above the sofa, a sloped skylight illuminated the library. During heavy rains, water would drip from the skylight’s bottom-right corner, landing precisely on the sofa’s left armrest and eventually causing that fading. When I met the Maestro in 1987, he asked me point-blank: “Does the skylight still drip?” Then, he confided that the dripping had ruined one of his paintings, which stood ready for a coat of varnish. Since it was slated for a major exhibition opening a few days later, he’d been forced to cover the damaged area with an off-white quadrilateral shape that resembled a stiffly starched ruff – an improbable yet functional addition, which, by serendipity, enhanced the canvas’s luminosity. It formed a dazzling fan-like shape, a Cubist plane echoing other geometries within the work. The painting in question was the first of his homages to Mantegna – a modern Expressionist reinterpretation of the late fifteenth-century frescoes in the Camera degli Sposi in the ducal palace in Mantua. It features a group of six figures and a dog, packed and flattened into an area of about forty-five square feet. The figures, seen frontally and in profile, are based on those of the Gonzaga family as painted by Mantegna and are characterized by swollen, deformed features and painted with swift, decisive brushstrokes. The work originated from a pencil sketch that was then extensively reworked. “In the late fifties [of the twentieth century], we all painted the same way,” the Maestro used to say, “invariably influenced by Picasso, the Mexican muralists, and the German Expressionists.” Yet not everyone possessed the same depth of artistic knowledge as he did: only one among the artists in his circle – the Maestro himself – had spent three years visiting Europe’s great museums, dedicating himself to copying masterpieces and learning techniques. The shared influences were evident, but so too were the differences, especially one: the Maestro’s debt to Piero della Francesca and Velázquez. The sketch for his homage to Mantegna reveals a trained hand, skilled at depicting the stern patriarch’s family including several of his numerous progeny, shown with large eyes, pursed lips, and upturned noses. However, in the painting, the plump, youthful portraits the Maestro had sketched undergo premature aging, shifting from roundness to angularity, from lushness to obesity, from serenity to gloom. Yet this transformation does not betray the painting’s Renaissance origins – or if it does, we see here both the deliberation of a translator and an unusual self-awareness for a 25-year-old Colombian artist.

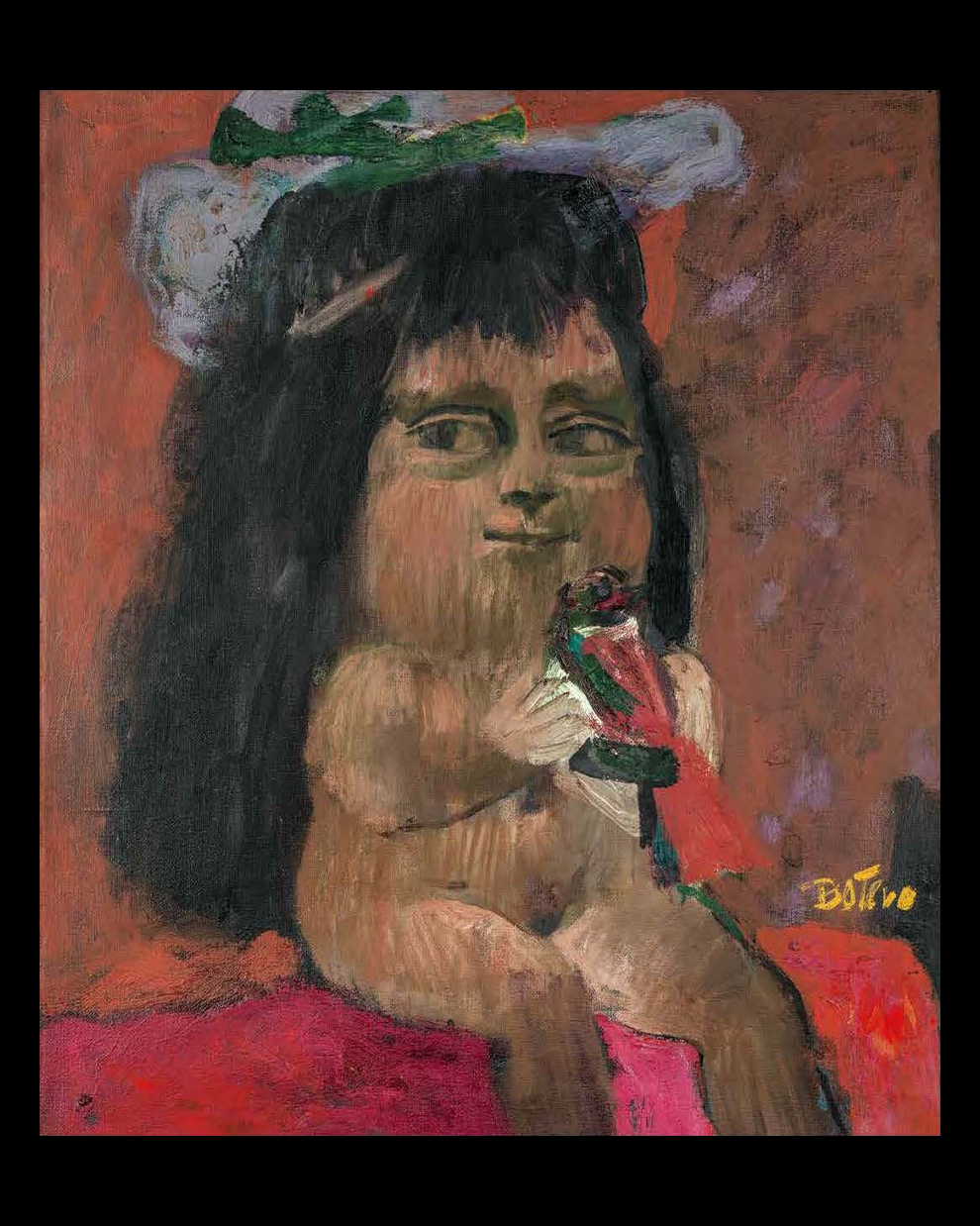

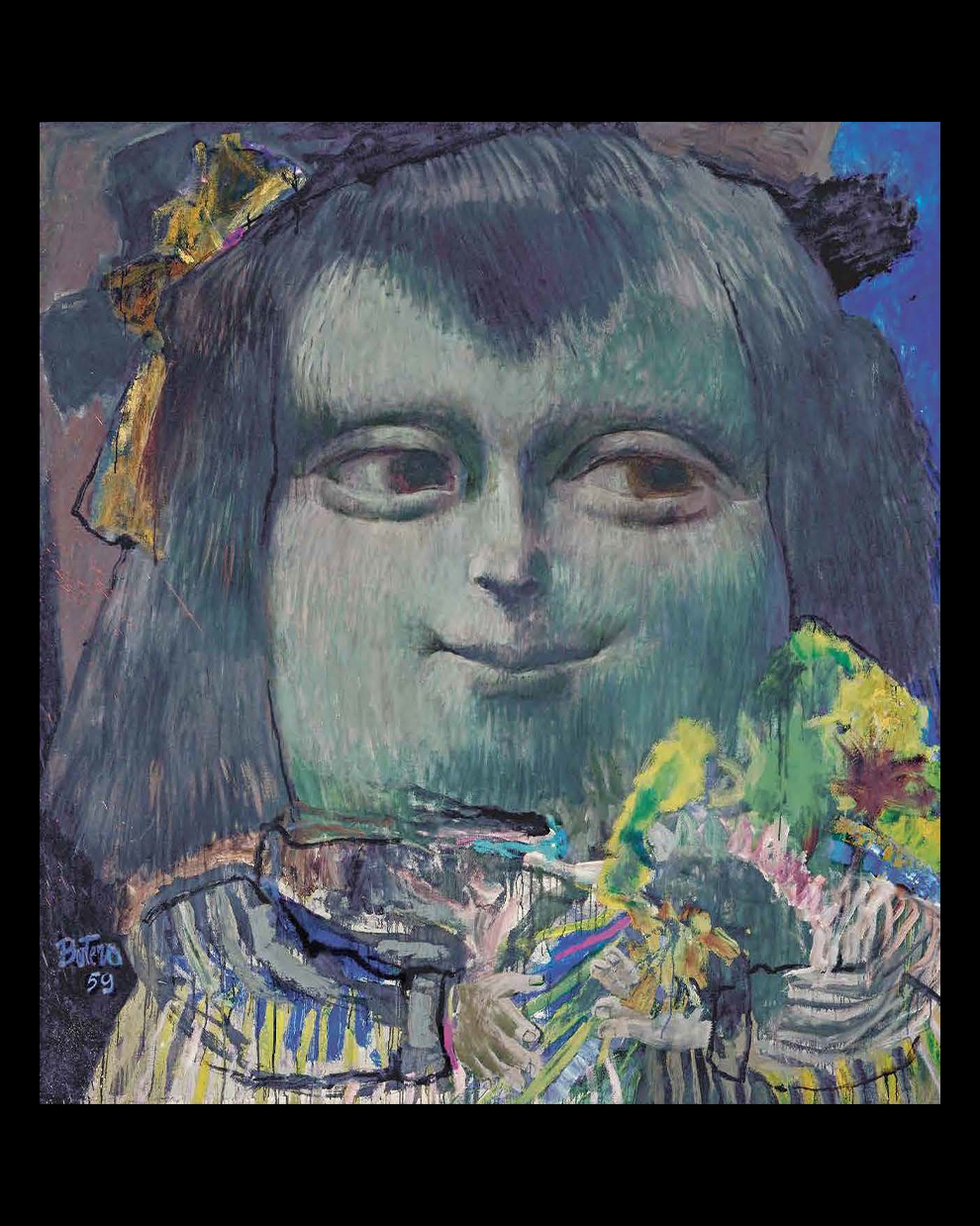

5. Despite his strong Paisa accent, the Maestro (to revert to our meeting of 1987) was clearly cosmopolitan – on the evening in question, he wore a black-and-white checked blazer tailored on Savile Row – and showed great ease when engaging with foreign guests. He had the magnetic gaze and goatee of a broodingly handsome beau ténébreux, but exuded a caustic irony that made one skeptical of his anecdotes. It was precisely for this reason that, at first, I refused to believe the story of the patched painting. I knew the attic had once been his studio, but I didn’t know – nor could I have imagined – that the drip from the skylight (which he had insisted upon installing against the architect’s advice) had impacted his career. Yet I was wrong to doubt him. At the time, among the volumes in the library were several green leather-bound albums, one of which contained photographs of the Maestro during the years when the attic served as his studio, roughly between 1956 and 1959. There were about ten photos, all taken by the same photographer, all set among the slightly uneven floorboards and exposed beams that I knew so intimately. One of them – this I discovered in the days following our meeting – held proof of the truth in his tale. On the left appeared the painter, a lanky, emaciated young man with sunken eyes, wearing a sweater and jeans; to his right was the expansive Homage to Mantegna, with the aforementioned patch clearly visible. Both the canvas and its artist were bathed in light streaming from the infamous skylight. In fact, the canvas rested on an easel fixed to a roof beam directly (and fatefully) beneath the skylight. The pale trapezoid – needless to say – was located precisely beneath the lower-left corner of the skylight’s frame. That persistent dripping had not only led to an unplanned retouching but was likely among the reasons that prompted the Maestro to abandon the studio – and to renounce Cubism. Indeed, once in Mexico, his style underwent a renewal, particularly noticeable in the second Homage to Mantegna, which was less angular and impetuous than the first. This evolution was most evident, however, in his female portraits inspired by the Mona Lisa: young women depicted half-length in elaborate attire or fully nude, smiling coyly or smirking. For twenty years, I had one of these works before my eyes, and I must confess that even today I still see her as pubescent in her red dress. It is precisely in these “twelve-year-old Giocondas” that the Maestro’s commitment to tactile values, as defined by Berenson, becomes apparent. Each of these figures, marked by a violent yet compressed dynamism, is like a chrysalis, representing an unfinished (though no less decisive) stage in the artist’s creative process – volumetric exercises in oil or pastel destined to metamorphose over time into monumental bronzes. Or are they, instead, mocking nymphettes who are only ostensibly immature? Either way, they are primal incarnations of the equation deformis formositas, ac formosa deformitas (“deformed beauty, and beautiful deformity”), which the Maestro, following in St. Bernard’s footsteps, placed at the core of his esthetic. Monstrosity, he sarcastically insinuates, is already evident in the adipose appearance of humans at their first emergence and persists, in varying forms, throughout the three ages of life. Lisa del Giocondo was no exception: the full face of the young wife bears traces of the chubby infant she once was. Childhood, he suggests, is not the season of grace and innocence but rather the era of deformation, during which toddlers transform into dwarfs. Not even Infanta Margarita Teresa escapes this common fate, which is perhaps why Velázquez placed her next to Mari Barbola, the court dwarf, in his iconic painting. This pairing, incidentally, also appears in the Camera degli Sposi, where Mantegna depicts the dwarf Lucia standing beside the seated marchioness – a combination faithfully echoed by the Maestro in his Homage. But while the characters in the Maestro’s drawing display healthy childlike features, in the final painting they seem to suffer from some endocrine condition. This shift not only marks the transition from healthy roundness to morbid obesity but also from flatness to volumetric depth. And it is precisely in the choice of volume as a formal and esthetic solution that tactile values come into play.

6. These elements, however, upon closer inspection, are already present in a portrait from 1956, created during the fervor of a love affair – a portrait in which the woman’s gaze becomes, as the saying goes, a “mirror of the soul.” At first glance, it seems like a conventional painting, yet it encapsulates the young Maestro’s trajectory in a nutshell – his engagement with the various ways in which the limits of realism were being tested in the twentieth century. The allure of Cubism is evident, but the inclination toward mimetic fidelity is stronger and ultimately prevails. Though vigorous, the brushstrokes convey timeless sentiments – refinement and attentiveness – faithful to the portraitist’s intent of capturing the subject’s natural grace rather than distorting the figure through stylistic interventions. The result is an elegant and nostalgic portrait, recalling a stanza by a poet of the Dolce Stil Novo: “Gentle and noble lady, / Whom Love has made my first mistress, / Show mercy, for I carry / Your image painted in my mind, lest I forget.” It is an image painted in order to remember, not an attempt to experiment with different modes of expression – a tribute not to this or that artistic genius, nor to the eternal feminine, but to a woman of flesh and blood, “gentle and noble.” At the same time, it is a prophetic portrait, anticipating the Maestro’s reconciliation with the tenets of figurative realism – without eschewing, however, the underlying esthetic qualities of deformation. The Maestro’s views on this subject were summed up in a few trenchant words – “In art, as long as you have ideas and think, you are bound to deform nature. Art is deformation” – turning on its head the classical axiom that the true artist is driven not by the instinct to imitate but by the instinct to perfect (see, for example, Kenneth Clark). In this portrait, the prevailing impulse is to transpose into forms and colors the image the painter “carries painted in his mind”; forms and colors, in turn, capable of conveying life-enhancing values – so perfect, in other words, that they enrich the esthetic sensibility of us, the viewers. The woman who sits for this portrait is motionless but not lifeless, enlivened by vibrant strokes that paradoxically emphasize her two-dimensionality – or, if you will, her lack of depth. I spent many hours attempting to grasp its truth, not the truth once sought by the fresh young painter regarding his subject, but the truth of the painting: those details that allow an image to attain artistic synthesis and endure in the mind. And after so much time spent looking, I caught the woman gazing at me: it was an intensely sorrowful gaze, like those of people who are no longer with us, and her eyes were slightly misaligned, like a crosseyed Venus. And I understood that the Maestro had read the works of Jacopo da Lentini.

7. But the late medieval poetry of the Stilnovisti was not really his preferred reading material. Among the photos in the album I discovered in 1987, a vertical shot depicts the 24-year-old Maestro in his studio. He is seated cross-legged on a butterfly chair, surrounded by upright or tilted canvases and frames that evoke a Constructivist mise en scène. His gaze is fixed, a cigarette hangs between his lips, and he has a small paperback in one hand. To be precise, it is a Doubleday Anchor Book, and he holds it open with his fingers. The cover displays the title and author: Aesthetics and History by Bernard Berenson, though neither the date nor the place of publication is visible. I take the liberty of describing this in detail because the book belongs to me, as do many other volumes from the Maestro’s early library (thus, I can confirm it was printed in 1954 in Garden City, N.Y.). I’m curious to know how the Maestro absorbed the teachings from this book – Mary Hemingway, for instance, famously declared that it gave her “greater pleasure than her favorite champagne,” which is saying something. And I wondered how far into the text he had read when he was interrupted by the photographer. The answer is relatively straightforward: one of the Maestro’s fingers serves as a bookmar. It is here that Berenson introduces the foundational concepts of his critical discourse, concepts that would later be explored in practical terms in the “jocund twelve-year-olds” and other works created after the Maestro’s trip to Italy. “I had the fortune of reading Berenson when I was eighteen,” he explained. “With his intellectual clarity, Berenson enabled me to understand what had, until then, been merely an inclination – a kind of intuitive preference.” When he encountered the ideas of the American connoisseur (whose prose, it must be said, is not particularly lucid), the Maestro had already observed the works of Giotto and the great Renaissance painters up close. This allowed him to empirically verify the validity of Berenson’s theories. What Aesthetics and History first taught him was the significance of volumetric effects within pictorial representation and their inseparability from “tactile values.” Yet, as with any initial infatuation, the Maestro later subjected these teachings to a tacit reassessment – without which, it must be added, his style would never have fully blossomed.

8. Bailarina was not yet five years old, measured 4 ft 9 inches at the withers, had a well-kept mane, gleaming coat, and restless eyes. “In many ways, she resembles you,” the Doctor had told the lovely young woman as he helped her mount the Passier trotting saddle, “and that’s why I’ve decided to give her to you as a gift.” Just weeks later, when the woman sought to claim her gift, the animal had vanished.

She walked the four sides of the paved portico with her head lowered, casting distracted glances at her reflection in the dark glass windows. Then, with a shudder, she turned decisively back toward the stable. Reaching the large double doors, Bailarina used her forehead as a battering ram and pushed until they cracked open. With a soft neigh, she entered what had, not long ago, been her beloved and exclusive lodging. She basked in the solitude of the long nave, unaware that the space had been transformed from a stable into a sanctuary of art, and emerged after barely two hours, leaving behind an astonishing amount of physiological traces (it has been reported that contentment accelerates the bodily rhythms of equines, making two hours of bliss for a foal equivalent to two listless days in the life of an adult horse). As for the swarm of horseflies that followed Bailarina into the old stable, it cannot be said with certainty that they were horseflies at all or that they constituted her usual entourage. It is worth noting that flies are uncommon at the heights of the cordillera. No one can say what emotions the ten or twelve painted canvases, now complete and set out along the nave to dry, might have stirred in Bailarina. The paintings had yet to be varnished and awaited the Maestro’s final brushstrokes. He was due to return from New York in a few days and had planned to immediately resume work. While the fantasies of a horse remain inscrutable, the reactions of a swarm of flies to the oil- and turpentine-scented, multicolored surfaces are easier to grasp – and indeed, they were not unlike Bailarina’s own: an astonishing number of excretions were scattered across the canvases and immediately absorbed into the still-moist fabric. The Maestro’s rage upon witnessing the devastation – a fact I learned on the evening I met him, roughly a year after the event – was only slightly less than that of Achilles. Without hesitation, he ordered the studio razed to the ground and the paintings destroyed.

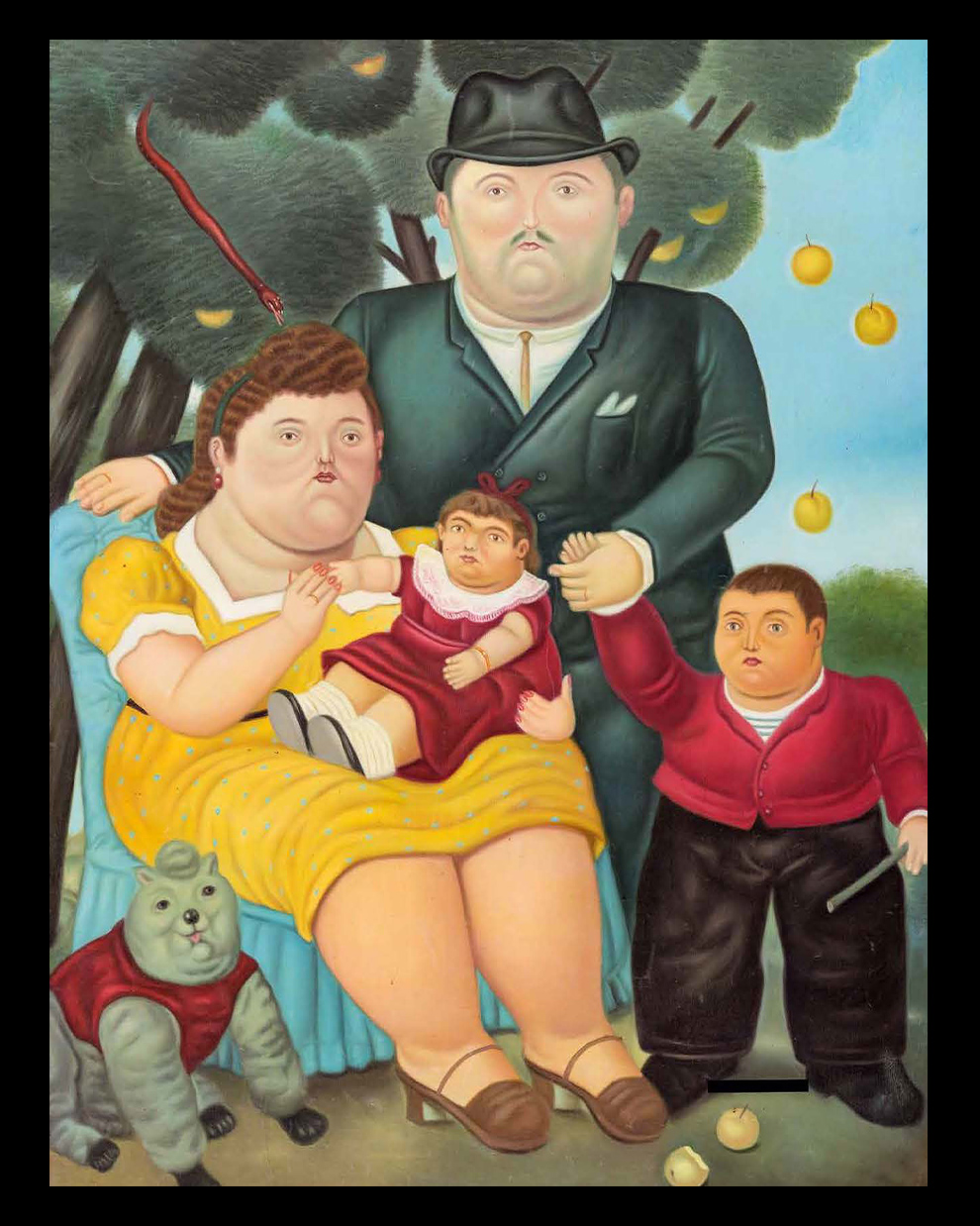

9. Néstor is a youthful-looking restorer who takes more pride in his bicycle (specifically, an Elops LD 900) than in the Veronese panel that came from a Uruguayan diplomat who had generously issued humanitarian visas during World War II. He also frames works for prominent collectors and artists, including, first and foremost, the Maestro. I hadn’t seen him in years, but we quickly started talking about bicycles. Then, perhaps influenced by recent exhibitions on the presence of flies in art, I asked him if there were any in the Maestro’s works. “Oh, absolutely!” he exclaimed. “They flit about in family groups, still lifes, floral compositions…” He paused to reflect and then added, “Their presence isn’t random: if nothing is random in psychology, imagine how deliberate it must be in art.” “Does it have symbolic meaning? Maybe scatological implications?” I probed. Néstor launched into a complex explanation: “The presence of flies isn’t symbolic but expressive, in that they introduce a sense of movement into an inert scene (such as a still life or a posed couple), contrasting with the stillness of the figures – or more precisely, with the flatness of the image. The flies circle around the characters and objects, and in doing so highlight their volume, their ‘mass.’ Odd as it may seem, thanks to the flies, the figures become sculptural. But for this effect to fully materialize, the flies themselves need to possess tactile qualities – physicality and movement – which is not the case in the Maestro’s paintings. After a few tentative efforts in the 1970s, the flies disappear from his works, reappearing only sporadically and for anecdotal purposes. From then on, he relied on obesity to achieve volumetric rendering, convinced that, though his paintings were flat, this quality could generate in viewers the ‘muscular and tactual sensations’ – to quote Berenson again – of three-dimensionality.” Néstor didn’t convince me, but I chose to keep quiet. In my opinion, the disappearance of flies was the result of a punitive measure against the horseflies that had accompanied Bailarina: in his anger, the Maestro had extended it to the entire genus Musca. After all, wasn’t it he, or someone acting on his behalf, who had operated the bulldozer that razed the old stables, burying their remains along with those of twelve oil paintings dotted with excrement? If Néstor had known, he’d have reached the same conclusion… and so he did. A few days after we met, a rather battered canvas arrived at his workshop, accompanied by a note identifying it as an “amateur copy” of a work by the Maestro housed in a Bogotá museum. It depicted a family group: a young bourgeois couple, two children, a dog (and a small snake), set against a wooded background. “A painting so well-executed it could pass for the original,” commented Néstor, “Same pigments, same texture, same multi-layered brushstrokes, same thin canvas, same ground.” An extraordinary vrai faux, distinguishable from the prototype only by its smaller dimensions, the absence of a reddish glaze on the characters’ faces, and the lack of a signature. Bewildered, my friend couldn’t let it go. With the help of an LED viewer, he examined the canvas inch by inch… until dark, minute stains emerged here and there beneath the varnish! Organic, unquestionably, and soon identified as the droppings of flying insects of the Diptera order. And that’s how the truth came to light: this anonymous, stained, poorly varnished canvas was the Maestro’s work – rejected due to the actions of a quadruped and a swarm of houseflies. Rejected and presumably destroyed, yet somehow spared, salvaged by some unknown person, it had now reappeared for reasons just as mysterious. As we puzzled over it, I thought of Bernard Berenson and his theory of tactile values, and I reflected on the pleasure of art and how, on one level or another, it is shared by all living creatures, including equines and muscids. And I recalled these verses by William Blake:

“Little fly / Thy summer play / My thoughtless hand / Has brushed away / Am not I / A fly like thee? / Or art not thou / A man like me?”

Giorgio Antei

translation by Laurel Saint Pierre, Antony Shugaar

All paintings reproduced on these pages are by Fernando Botero Angulo (1932–2023).