With this edifying tale, Cervantes offers us profound insight into the nature of both human beings and stones. Mechanically testing stones matters less than clearly perceiving their qualities: their very appearance speaks to us on a basic level, as does the way they let us read them, regardless of their specific physical features. Franco Maria Ricci, who was a geologist before he founded this magazine, may perhaps have guessed (indeed, must have known) that this kind of bond was a crucial link in the chain between the mineral kingdom and the domain of art. Roger Caillois – an “Immortal,” that is to say, a member of the Académie Française – who could read stones like the back of his hand, thought so too. The use of the verb “read” may seem ambiguous here, or at least polysemic: we can read a book, an alphabet (whether known or unknown), a text message, a tarot deck, the future, both omens and portents, another person’s expressions or intentions, the results of a lab test, a diary, or even the human soul. Roger Caillois could read stones in all these ways, at the very least, and most likely in others still. He also collected them.

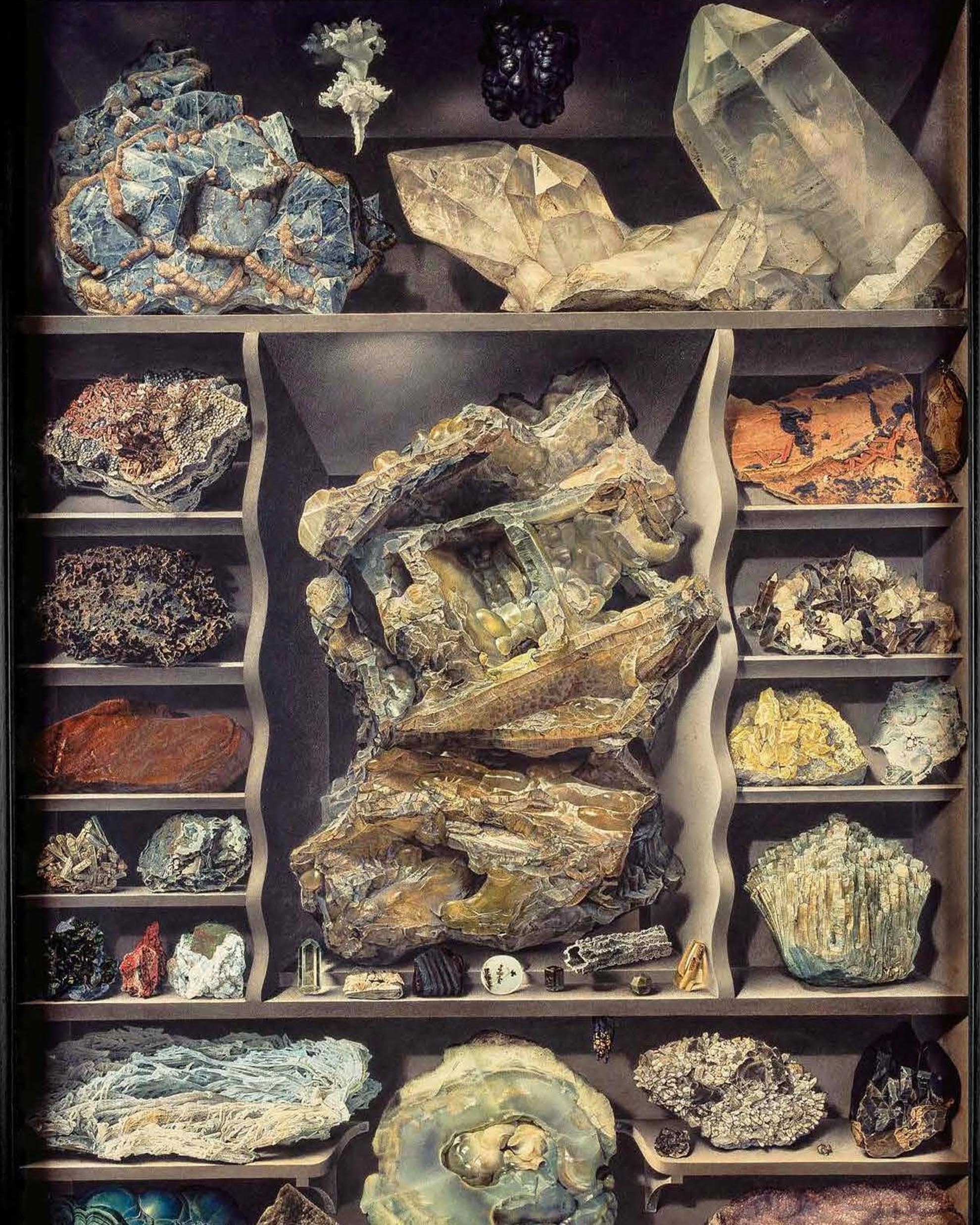

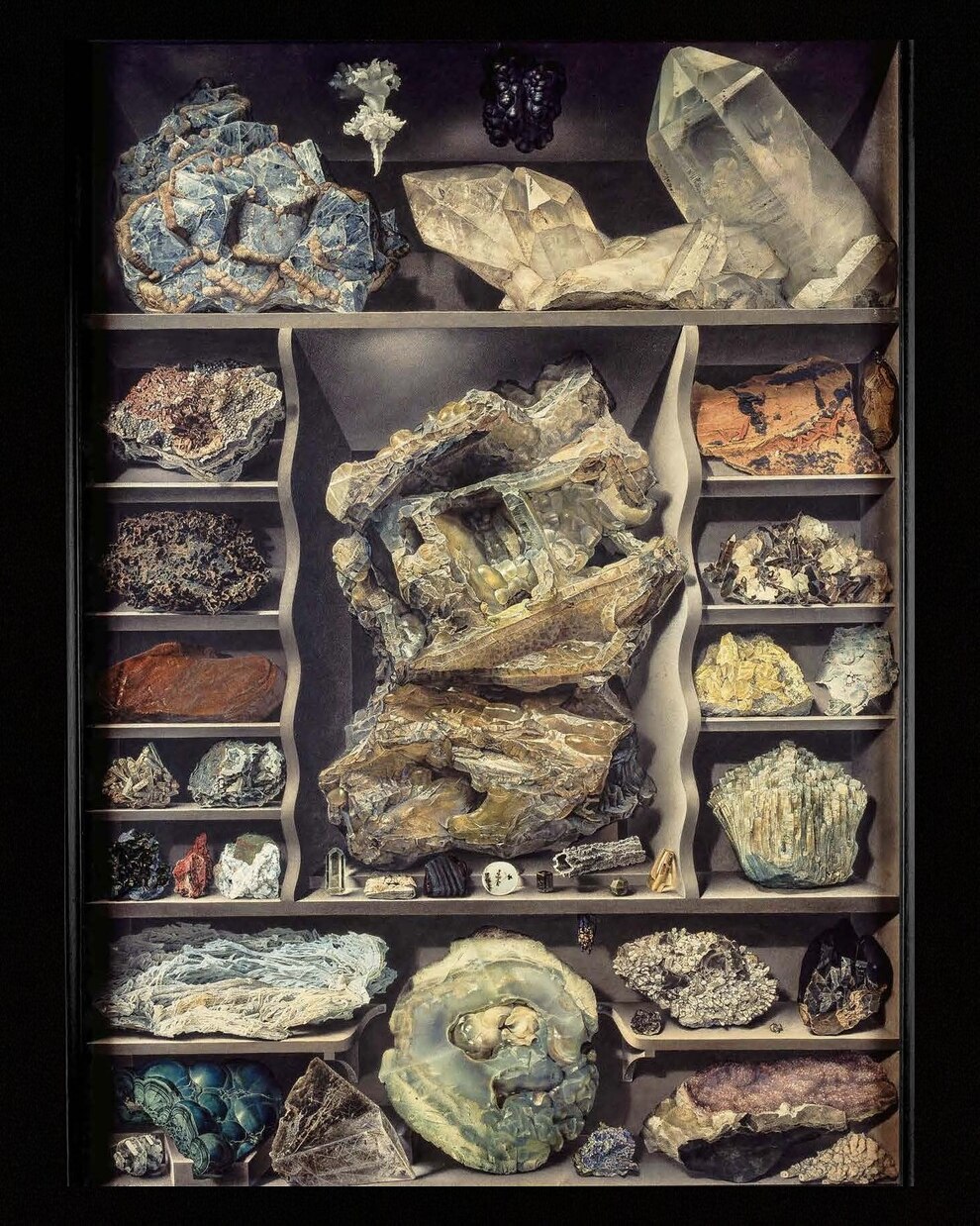

Part of his collection was donated by Van Cleef & Arpels to the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. A number of these wonderful objects are currently included in an exhibition at the Villa Medici in Rome; Franco Maria Ricci Editore is devoting a new book to them, and the following article is an extract from it.

Pietro Mercogliano

translation by Laurel Saint Pierre, Antony Shugaar

These consist of subtle and ambiguous signals reminding us, through all sorts of filters and obstacles, that there must be a preexisting general beauty vaster than that: perceived by human intuition – a beauty in which humans delight and which in their turn they are proud to create. Stones – and not only them but also roots, shells, wings, and every other cipher and construction in nature – help to give us an idea of the proportions and laws of that general beauty about which we can only conjecture and in comparison with which human beauty must be merely one recipe among others, just as Euclid’s theorems are but one set out of the many possible in a total geometry.

In stones the beauty common to all the kingdoms of nature seems vague, even diffuse, to humans, beings themselves lacking in density, the last comers into the world, intelligent, active, ambitious, driven by an enormous presumption. They do not suspect that their most subtle researches are but an exemplification within a given field of criteria that are ineluctable, though capable of endless variation. Nonetheless, even though they neglect, scorn, or ignore the general or fundamental beauty which has emanated since the very beginning from the architecture of the universe and from which all other beauties derive, they still cannot help being affected by something basic and indestructible in the mineral kingdom: something we might describe as lapidary that fills them with wonder and desire.

This almost menacing perfection – for it rests on the absence of life, the visible stillness of death – appears in stones so variously that one might list all the endeavors and styles of human art and not find one without its parallel in mineral nature. There is nothing surprising about this: the crude attempts of those lost creatures, humans, could not cover more than a tiny part of the aesthetics of the universe. No matter what image an artist invents, no matter how distorted, arbitrary, absurd, simple, elaborate, or tortured they have made it or how far in appearance from anything known or probable, who can be sure that somewhere in the world’s vast store there is not that image’s likeness, its kin or partial parallel?

Even setting such similarities aside, human beings are attracted and amazed by many mineral formations: spiny tufts of quartz; the dark caves of amethyst geodes; shiny slabs of variscite or rhodochrosite agate; fluorine crystals; the golden, many-sided masses of pyrites; the simple, almost unsolicited curve of jasper, malachite, or lapis lazuli; any stone brightly colored or pleasingly marked.

Connoisseurs, in such cases, admire the qualities of a material that is constant and unchanging: purity, brilliance, color, structural rigor – properties inherent in each kind and present in every example. Their values are intrinsic, without external reference. The price a purchaser pays for them depends on weight, rarity, the amount of work involved, just as with a length of satin or brocade, a bar of refined metal, or a gem. Like such commodities, these stones are exchangeable, since there is no difference between one of them and another example of the same kind, size, and quality.

The whole picture changes when singularity is what is sought after. The stone’s inherent qualities and special geometry are no longer of primary concern, perfection no more the sole or even the main criterion. This new beauty depends much more on curious alterations brought about in the stone itself by means of metallic or other deposits, or on changes in its shape due to erosion or serendipitous breakage. Some pattern or peculiar configuration appears in which the imaginative observer descries an unexpected, in this context an astonishing and almost shocking copy of an alien reality.

Moreover, such a duplicate is not a copy; it is not born of an artist’s talent or a forger’s skill. It has been there always: we only had to find our way into its presence. Ordinary rocks as well as various types of mineral specimens make up this prey of Pan. In China, poets and painters would see in a clef stone a mountain with its peaks and waterfalls, its caves and paths and chasms. Collectors ruined themselves to possess crystals in whose translucent depths they discerned mosses, grasses, and boughs laden with flowers or fruit. An agate may shadow forth a tree, several trees, groves, a forest, a whole landscape. A piece of marble can suggest a river flowing among hills; the clouds and lightning flashes of a storm, thunderbolts and the grandiose plumes of frost; a hero fighting a dragon; or a great sea full of fleeing galleys, like the scene a Roman saw reflected in the eyes of an Eastern queen already planning to betray him.

One kind frequently depicts a burning town, with its towers and steeples and campaniles crashing down. On the agate of Pyrrhus antiquity made out Apollo with his lyre, surrounded by the muses, each with her special attributes. In the seventeenth century Gaffarel, Richelieu’s librarian and the king’s chaplain, devoted a whole weighty volume to gamahés, healing talismans made of stones inscribed with natural astrological hieroglyphs. Princes and bankers of the same period collected unusual specimens sought out for them at great expense by the numerous agents of specialist merchants. Learned men, among them Aldrovandi and Kircher, divided up these marvels into families and types according to the images they managed to distinguish in them: Moors, bishops, lobsters, streams, faces, plants, dogs, fishes, tortoises, dragons, death’s heads, crucifixes – everything a mind bent on identification could fancy. The fact is that there is no creature or thing, no monster or monument, no happening or sight in nature, history, fable, or dream whose image the predisposed eye cannot read in the markings, patterns, and outlines found in stones. The more unusual, definite, and undeniable the image, the more the stone is prized. Stones that offer rare and remarkable likenesses are regarded as wonders, almost miracles. They should not exist, and yet they do, at once impossible and inescapable. At the same time, they are treasures, the result of thousands upon thousands of chances, the winning number in an infinite lottery. They owe nothing to patience, industry, or merit. They have no market rate or price. Their value is not commercial and cannot be calculated in any currency; it laughs both at the gold standard and at purchasing power. It is not convertible into labor or goods. It depends solely on the covetousness, pride, and competitiveness generated by the desire to possess or the pleasure of possessing them. Each stone, as unique and irreplaceable as a work of genius, is a valuable at once pointless and priceless, with which the laws of economics have nothing to do.

That being the case, they are frequently regarded as amulets and talismans. The owner of such a wonder, brought into being, discovered, and delivered into their hands through an inconceivable concatenation of chances, easily comes to believe that it could have come to them only through some special intervention of fate. They grow passionately attached to it, think of it as a guarantee of health and success. But we are not concerned here with the magical virtues superstition attributes to stones inscribed with images, nor even with the joyful gloating of their owners.

In some Eastern traditions insight may be obtained from the strange shape or pattern in a gnarled root, a rock, a veined or perforated stone. Such objects may resemble a mountain, a chasm, a cave. They reduce space, they condense time. They are the object of prolonged reverie, meditation, and self-hypnosis, a path to ecstasy and a means of communication with the Real World.

I leave such fabulous emotions to their fate, concerning myself only with the present-day competition between the products of nature and the works of painters and sculptors, whether nature’s offerings appear to represent something or are pure sign. Artists have added to them or merely signed and framed them as they were, thus putting them in the same category as pictures. So they must have fund some correspondence or element in common between their own creations and these works executed by no one.

The juxtaposition should be revealing. At the very least it brings out some strange reversals. We have seen modern painters first give up trying to reproduce their models exactly, then abandon models altogether and eschew any kind of representation. And those markings on stones are considered most interesting which do not represent anything. Yet at the same time those rarer stones that do seem to depict something are coming back into favor. It is strange to think that nature, which can neither draw nor paint any likeness, sometimes creates the illusion of having done so, while art, which has always been successful at resemblances, renounces its traditional, almost inevitable and “natural” vocation and turns to the creation of such forms as nature itself abounds in – mute, unpremeditated, and without a model.

This inversion in the order of things seem simultaneously to reveal and to conceal a problem. To clarify the data of the problem, though I do not promise to find its solution, I shall try to define the ways in which nature sometimes gives us the impression of representing something. I should also like to explain the strange attraction of these manifestly illusory likenesses.

The vision the eye records is always impoverished and uncertain. Imagination fills it out with the treasures of memory and knowledge, with all that is put at its disposal by experience, culture, and history, not to mention what the imagination itself may if necessary invent or dream. So the imagination is never at a loss when it comes to making something rich and compelling out of a subject that might almost seem an absence of all life and significance.

The image which results from the combination of those shimmering colors […] induces in the beholder the same surprise as that produced by a sea louse, a water scorpion, an anteater, or any other creature left behind at some crossroads of evolution, almost a warning.

One day some bold being invents – or has invented in him – a form which may be valid at the time but which is soon set aside in favor of a simpler and more elegant solution. The brave discovery survives through inexplicable negligence on the part of those stern powers that usually eliminate the fantasies of a moment, even though that moment may last thousands of years. Such forms endure only to bear witness to life’s mistakes, to remind nature of its monsters, its botched jobs, its blind alleys.

The strange markings in an agate lead me suddenly into wild extrapolations, seeking, in the obscure workings taking place within a stone at the dawn of time, traces of similar abandonments. By their very strangeness the failures they perpetuate become for me so many speaking portents, or at least emblems. They somehow announce the coming, in the distant future, of a species that makes mistakes, a being in whom freedom and imagination, together with their necessary disappointments, will be more important than successes due to infallible and inevitable mechanics. They presage new powers, imperfect but creative.

Such aberrations exert a special fascination on humankind. They seem to be manifestations par excellence of what I have ventured to call natural fantasy. Perhaps their undeniable, unfailing, and yet mysterious attraction lies in the fact that, through some dim reversal, they assert the right a doomed nature has won to the gratitude of its latest, grudging heir.

Humankind has unknowingly inherited a capital made up of immemorial audacities, unsuccessful risks, and ruinous wagers, an endeavor which, though it long persisted in vain, was one day to foster in us a new, rebellious grace, combining hesitation, calculation, choice, patience, tenacity, and challenge. I can conceive of some divinity, some total intelligence that is panoramic in the widest sense of the word, capable of contemplating in one purview this infinity of vicissitudes and their inextricably complex interactions. Such hypothetical cosmic consciousness would not be surprised at the existence of a lasting and inalienable collusion between this series of fertile false starts and their ultimate beneficiary. It would seem to it inevitable that a secret affinity should allow the heir to recognize, among the daunting mass of nature’s ventures, those which, though they did not succeed, opened up, through their very failure, a glorious way ahead.

Life appears: a complex dampness, destined to an intricate future and charged with secret virtues, capable of challenge and creation. A kind of precarious slime, of surface mildew, in which a ferment is already working. A turbulent, spasmodic sap, a presage and expectation of a new way of being, breaking with mineral perpetuity and boldly exchanging it for the doubtful privilege of being able to tremble, decay, and multiply.

Obscure distillations generate juices, salivas, yeasts. Like mists or dews, brief yet patient jellies come forth momentarily and with difficulty from a substance lately imperturbable: they are evanescent pharmacies, doomed victims of the elements, about to melt or dry up, leaving behind only a savor or a stain.

It is the birth of all flesh irrigated by a liquid, like the white salve that swells the mistletoe berry; like the semisolid in the chrysalis, halfway between larva and insect, a blurred gelatin which can only quiver until there awakens in it a wish for a definite form and an individual function. Soon after comes the first domestication of minerals, the few ounces of limestone or silica needed by an undecided and threatened substance in order to build itself protection or support: on the outside, shells and carapaces, and on the inside, vertebrae that are immediately articulated, adapted, and finished down to the last detail. The minerals have changed their employ, been drawn from their torpor, been adapted to and secreted by life, and so afflicted with the curse of growth – only for a brief spell, it is true. The unstable gift of sentience is always moving from place to place. An obstinate alchemy, making use of immutable models, untiringly prepares for an ever-new flesh, another refuge or support. Every abandoned shelter, every porous structure combines to form, through the centuries and the centuries of centuries, a slow rain of sterile seeds. They settle down, one stratum upon another, into a mud composed almost entirely of themselves, a mud that hardens and becomes stone again. They are restored to the immutability they once renounced. Now, even though their shape may still occasionally be recognized in the cement where they are embedded, that shape is no more than a cipher, a sign denoting the transient passage of a species.

Unceasingly, the microscopic roses of diatoms, the minute lattices of radiolaria, the ringed cups of corals like tiny bony disks with countless thin spikes resembling circles of converging swords, the parallel channels of palms, the stars of sea urchins – all sow seeds in the depths of the rock: the seeds of symbols for a heraldry before the age of blazons.

Meanwhile, the tree of life goes on putting out branches. A multitude of new inscriptions is added to the writing in stones. Images of fishes swim among dendrites of manganese as though among clumps of moss. A sea lily sways on its stem in the heart of a piece of slate. A phantom shrimp can no longer feel the air with its broken antennae. The scrolls and laces of ferns are imprinted in coal. Ammonites of all sizes, from a lentil to a millwheel, flaunt their cosmic spirals everywhere. A fossil trunk, turned jasper and opal like a frozen fire, clothes itself in scarlet, purple, and violet. Dinosaurs’ bones change their petit-point tapestries into ivory, gleaming pink or blue like sugared almonds.

Every space is filled, every interstice occupied. Even metal has insinuated itself into the cells and channels from which life has long since disappeared. Compact and insensible matter has replaced the other kind in its last refuge, taking over its exact shapes, running in its finest channels, so that the first image is set down forever in the great album of the ages. The writer has disappeared, but each flourish – evidence of a different miracle – remains, an immortal signature.

Roger Caillois

translation by Laurel Saint Pierre, Antony Shugaar

All of the stones in the Caillois collection featured in this article are now at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris.

NOTES TO THE IMAGE

“Larva” (chalcedony)

Probably from Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

Seminodular, sawn and polished, 9.5 x 10 cm

Gift of École Van Cleef & Arpels des Arts Joailliers, 2017

Agate with curvilinear diamond shape

From Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Thin cross-section, sawn and polished, 11 x 16 cm

Caillois Donation, 1984-1985

“Royal Calligraphy” (onyx)

Probably from Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Block with polished surface, 14 x 10 cm

Gift of École Van Cleef & Arpels des Arts Joailliers, 2017

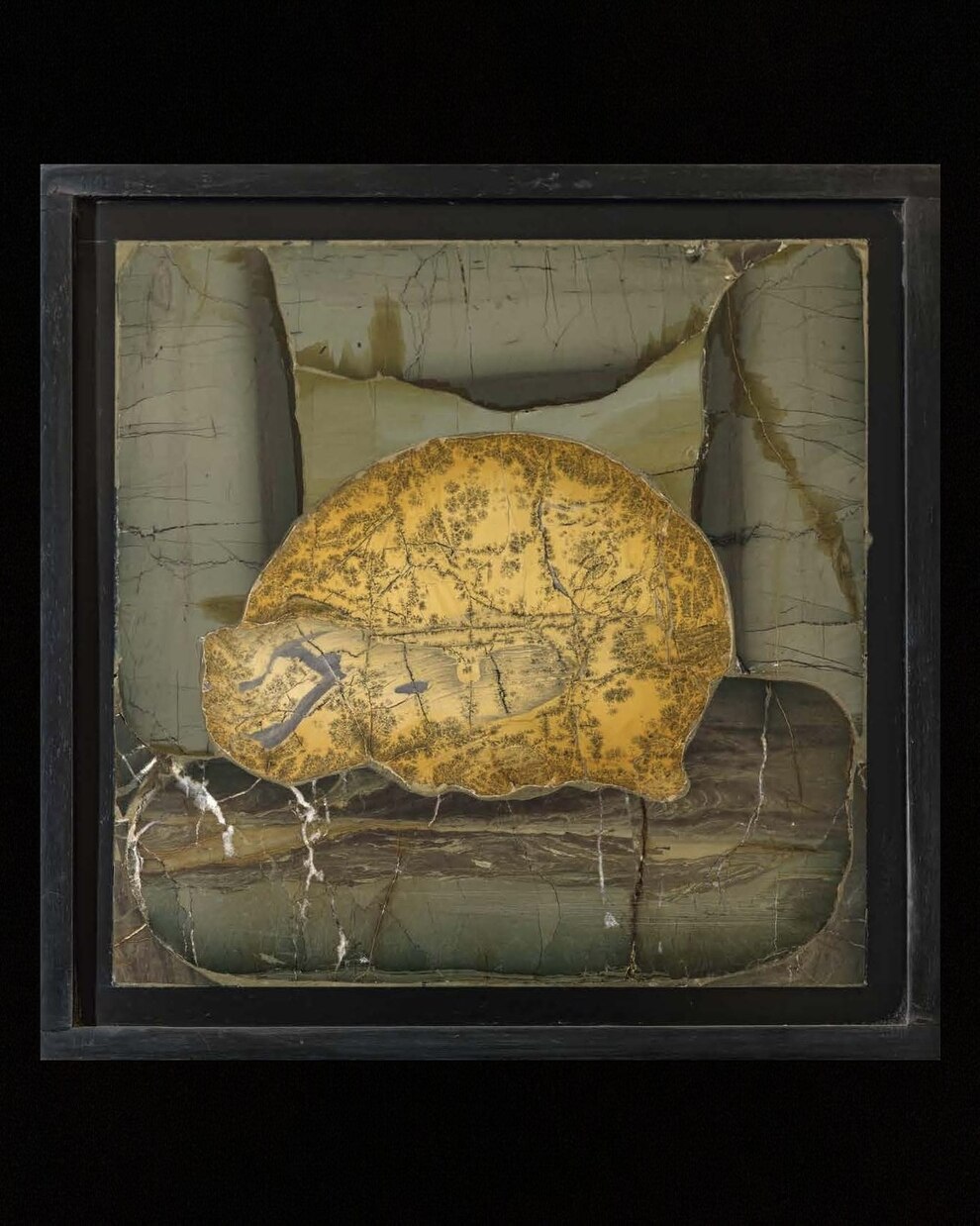

Septarian

From Otzenhausen, Saarland, Germany

Seminodular, sawn and polished, 9.6 x 9 cm

Gift of École Van Cleef & Arpels des Arts Joailliers, 2017

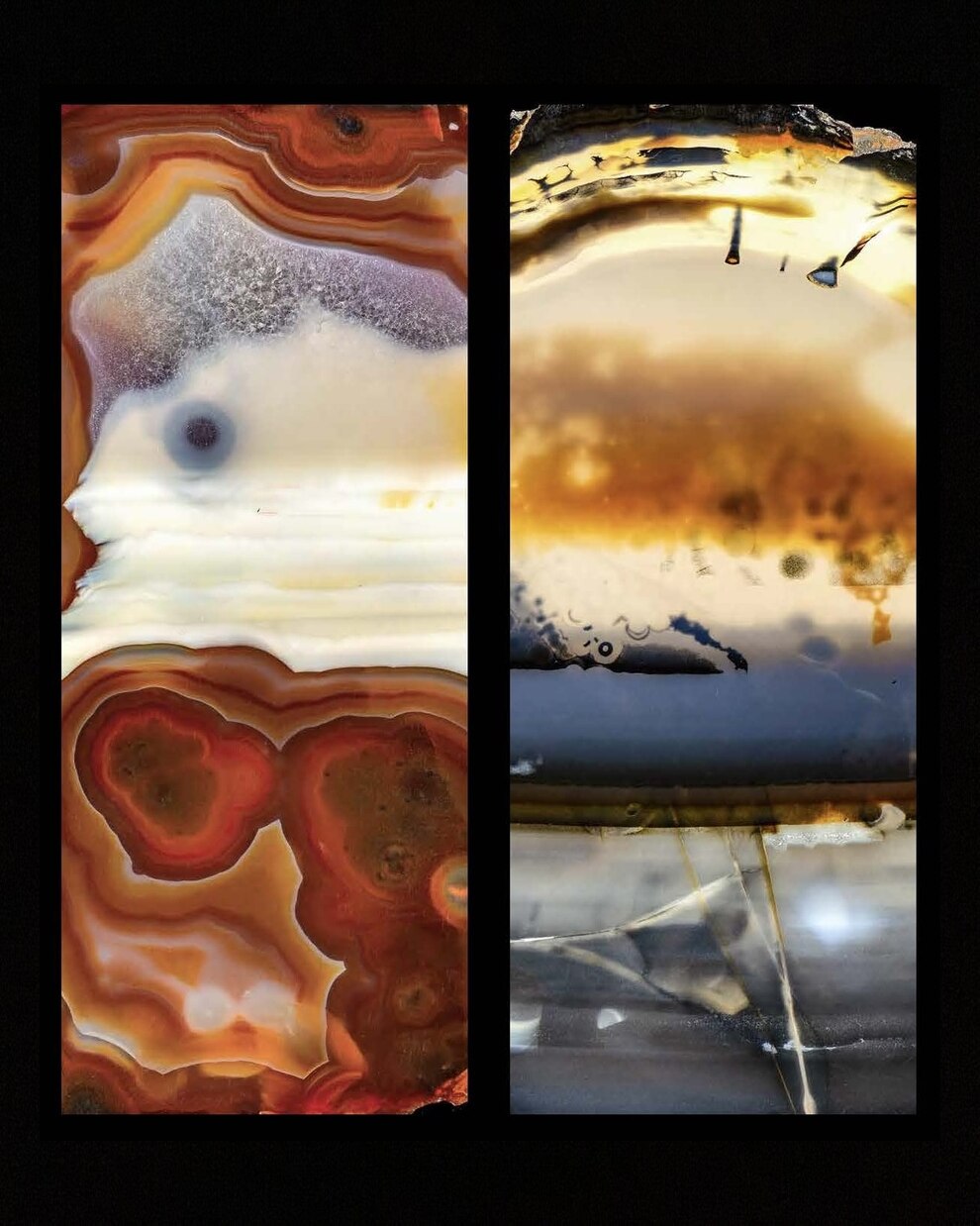

“Ghost” (agate)

From Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Thin cross-section, sawn and polished, 19 x 23 cm

Caillois Donation, 1984-1985

Wounded Agate

Probably from Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Thick segment, sawn and polished, 30 x 34 cm

Caillois Donation, 1988

Polyhedric agate

From Garguelo Farm, Paraíba, Brazil

Thin cross-section, sawn and polished, 11.7 x 14.4 cm

Caillois Donation, 1984-1985

Agate

Probably from Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Thin cross-section, sawn and polished, 15 x 16 cm

Caillois Donation, 1984-1985

“La Vetta” (Paesina agate)

Probably from Chihuahua, Mexico

Nodule, sawn and polished, 9 x 9.5 cm

Gift of École Van Cleef & Arpels des Arts Joailliers, 2017

“Monster” (quartz and chalcedony)

From an unknown location, U.S.

Nodule, sawn in half and polished, 12.6 x 11.2 cm

Gift of École Van Cleef & Arpels des Arts Joailliers, 2017

“Skeletal Monster” (septarian) Lithophysical rock of volcanic origin (?)

Probably from Black Rock Desert, Nevada

Seminodular, sawn and polished, 12 x 11 cm

Gift of École Van Cleef & Arpels des Arts Joailliers, 2017

“Calligraphy” (onyx)

Probably from Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Thin cross-section, sawn and polished, 14 x 12 cm

Caillois Donation, 1984-1985

Variscite

From Little Green Monster Mine, Fairfield, Utah

Seminodular, sawn and polished with carnallite (yellow) and cardite (white), 17 x 19 cm

Caillois Donation, 1984-1985

Quartz variety rock crystal with onyx “eyes”

From Artigas, Uruguay

Slab, sawn and polished, 23 x 25 cm

Caillois Donation, 1984-1985

“Oakstone” (baryte)

From Arbor Low, Derbyshire, England

Thick concretion, polished on one side, 23 x 29 cm

Caillois Donation, 1984-1985

“Hatching Bird” (chalcedony)

Agate, on flint

Probably from Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Very thick cross-section, 15 x 23 cm

Caillois Donation, 1984-1985

“Mask” (liddicoatite), turmaline family

From Madagascar

Thick cross-section, polished, 24 x 27 cm

Caillois Donation, 1984-1985

Chalcedony

From Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Seminodular, sawn and polished, 9.2 x 9.5 cm

Gift of École Van Cleef & Arpels des Arts Joailliers, 2017